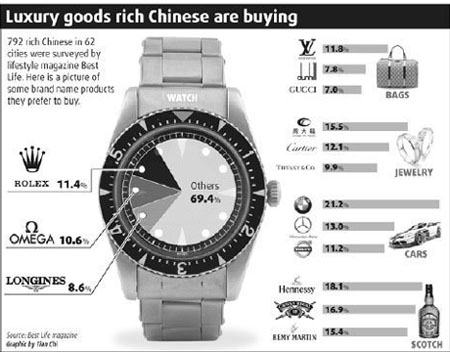

The country's widening income disparity is considered to be one of its most pressing social problems, with the average income of 20 percent of the richest Chinese families 17 times higher than the poorest households, the CASS reported in its 2009 Blue Book on Chinese Society.

Thursday, June 18, 2009

Material Handling Guides & Data

Material Handling Guides & Data

Assistance with your racks, conveyors, shelving, and more

Cross-Dock Planning

Cross-Dock Planning

Cross-docking is the process of moving goods straight from receiving to shipping to avoid unnecessary handling in a warehouse operation.

Execution of cross-docking can be planned or opportunistic. Opportunistic cross-docking occurs as part of the warehouse operation when outbound orders are matched with actual received quantities. This is often referred to as pick-on-receipt. Planned cross-docking is a pre-defined link between inbound and outbound, which directs what the warehouse should do.

Planned cross-docking is either defined by the host system or at the supply chain execution level. If done by the host, inbound order lines are linked to outbound order lines (including quantity required) through the inbound order.

On supply chain level, the cross-dock planning solution looks across nodes in the supply chain to determine which ASNs or inbound orders are to be cross-docked.

Capabilities

- Workbench for selecting inbound orders and ASNs and assign cross-dock links and quantities to outbound orders – automatically or by user decision

- Supports definition of cross-dock links on license (container) or order quantity level

- Maintain and release cross-dock links

- Configurable business rules for setting conditions for cross-dock proposals, including optional authorization steps

- User-defined rules can include criteria for which items are eligible for cross docking, how to select outbound order line candidates, and how to allocate quantities to order lines (e g consider customer priority when short of supply).

Benefits

- Increased use of cross-docking reduces handling costs in warehouses

- Higher turnover rates and shorter lead time by better coordination of supply and demand

- Improved ability to deal with shortage situations and rationing decisions

- Use cross-dock planning to re-route goods in-transit in transportation hubs to match latest market demand

Cross docking

Cross docking is as old as distribution but the issues associated with staging over the road (OTR) trailers and developing time critical delivery and shipping schedules have been replaced with simpler, more efficient methods. LoadBank International uses advanced bi-directional unit load conveyor staging to accommodate multiple receiving lanes and multiple shipping lanes all within close proximity of the OTR trailers. This allows greater flexibility in scheduling and lowers labor, space and transport-equipment costs.

Energizing Your Warehouse New Strategies For Greater Efficiency

Energizing Your Warehouse New Strategies For Greater Efficiency  In a tough economy, the universal battle cry is, "Do more with less!" We're all looking for new ways to squeeze a few more dollars, or a few more hours, from our operations while also delighting customers with ever-better service. In many cases, we're trying to achieve those goals while saving energy and reducing our environmental impact. Warehouse operators can employ many excellent strategies to boost efficiency: warehouse management systems, wireless communications systems, materials handling automation, and well-designed cross-docking, for starters. Companies also are applying techniques that you might not have heard about before. Here's how some logistics professionals are making their warehouses smarter, faster, greener, and more economical. LIGHTS, ACTION One simple technique for saving energy and cutting costs in a distribution center is to replace older lighting systems with high-intensity fluorescents. Warehouses traditionally have used mercury vapor lamps, which give off a bluish light, or sodium halide lights, which have a yellow cast, says Geoff Sisko, assistant vice president at TranSystems, a logistics consultancy in Woodbridge, N.J. Both types of bulb cast a cone-shaped light, making them a less-than-efficient warehouse solution. "With these bulbs, items high up in the racks are cast in shadow," Sisko says. "And low down on the floor, wasted light spills into areas that are covered by racks." In addition, such lights take a minute or two to achieve full brilliance. "They're also power hogs," Sisko adds. Many companies are retrofitting warehouses with T5 fluorescent bulbs and fixtures (T5 refers to the diameter of the bulb, 5/8 of an inch, in this case). These bulbs emit a lot of light, and because of their horizontal shape, they cast it in a linear pattern. "Arranging the lights correctly can provide good light from the top of the racks to the bottom along the aisles. And in open space, the lights can be positioned to distribute lighting evenly," Sisko says. Officials at Lion Brand Yarn Company, the oldest yarn brand in the United States, were so pleased with the fluorescents they installed in a Carlstadt, N.J., warehouse five years ago, they're now retrofitting a second building with that technology as part of a major renovation. "We currently use old-style fluorescent bulbs in the DC's ceiling," says Marty Leiderman, Lion Brand's distribution manager. The lighting contractors have specified T8 bulbs, which measure one inch in diameter. "The contractors are tailoring the light to the application we need," Leiderman says. "As a result, we'll have the proper amount of even lighting throughout the building." The new fixtures and bulbs are more energy efficient than the equipment that was available when the building was erected more than 30 years ago. "We get better light cheaper," Leiderman notes. Lion Brand expects to net a return on its investment in the new fixtures in less than two years. Some companies are going one step further and using motion detectors to control their fluorescent lighting. "If the detectors don't sense movement in an aisle for a predetermined amount of time, the lights shut off, and only a few bulbs stay on to provide minimum light," Sisko explains. "As soon as somebody moves into the aisle and motion is detected, the lights come back on." Another energy-saving technique that can be tied to a fluorescent lighting system is "light harvesting." When bright sunlight enters a room, a sensor sends a signal to a switch to dim the lights. When clouds roll in or the sun moves to the other side of the building, the fluorescent lights grow brighter. It has only recently become possible to control fluorescent fixtures in this way, Sisko notes. This technique is obviously best suited to buildings with large windows -- not a common warehouse feature. "Manufacturing plants currently use it, and schools and offices could use it," Sisko says. A warehouse could install such a system in areas near the loading docks, which do get outside light. If anyone is going to find a practical way to harvest light in a warehouse, it might as well be a company that makes its products from the fruits of the harvest. When Eden Foods, a Clinton, Mich.-based purveyor of organic foods, built an addition to its warehouse last year, it ran a five-foot-high window made of polarized plastic around the top of the facility. "The polarized plastic reduces the amount of lighting needed in the building," says Michael Potter, Eden's president and chairman. "It also lets in warmth in the winter and blocks the sun in the summer to minimize energy consumption." Optimizing the light and other elements to reduce the impact on the earth is part of Eden's corporate culture. So when it came time to build the 72,000-square-foot addition, Potter opted to follow guidelines established by the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Green Building Rating System. Buildings earn LEED certification for attaining goals in sustainable site development, water savings, energy efficiency, materials selection, and quality of the indoor environment. The addition, completed last year, incorporates recycled steel, highly efficient lighting, and a plumbing system that includes low-flush toilets. Eden also installed a bright white roof designed to reflect light and heat back into space, rather than absorbing it and contributing to global warming. In the near future, Potter hopes to make the warehouse even more sustainable by adding alternative energy sources, such as solar panels or a wind turbine. "Solar panels are becoming increasingly more cost effective," he says. A vendor exhibiting a windmill at a recent natural products expo told Potter he could build one sized to Eden's needs for $10,000. "That's a reasonable price," Potter says. "A significant return on investment and a positive impact on energy consumption with windmills is affordable, even for us." GOING UP Another way to achieve new heights in warehouse efficiency might be, simply, to achieve new heights. In crowded Asian cities, for example, vertical warehousing helps some companies beat the high cost of land, cut transportation costs, and reduce the operation's environmental impact. Multi-story distribution centers haven't yet caught on in the United States, but that could change, says Steve Campbell, senior vice president, director of environmental and development services at AMB Property Corporation, San Francisco. "Multi-story facilities are being discussed at length in the Los Angeles port area, and in the New York/New Jersey market," Campbell says. Officials at those ports are looking for ways to provide adequate distribution capacity in areas where there's little room left to expand. AMB owns, operates, and develops industrial real estate in the Americas, Europe, and Asia, and its portfolio includes about eight million square feet of multi-story warehouse space. Tenants of AMB's vertical warehouses include logistics service providers Exel, Expeditors International, BAX Global, and FedEx. Some shippers also have embraced the concept, Campbell says. A multi-story warehouse allows a company to operate in a dense urban area, rather than locating miles from the population center. That strategy offers several benefits. First, it shortens transit time to customers. "Companies in dense urban areas tie up a significant percentage of total operating cost in transit time," Campbell says. "When they start to cut transit times, efficiency soars." The second benefit is environmental; shorter trips burn less fuel. Also, it's easy to design "green" features into a facility that supports dense usage on a small site. Third, a multi-story warehouse offers much more usable floor space per square foot of land, a real boon in a city where land is expensive. "A typical floor-area ratio (FAR) in the United States is about 35 to 40 percent," Campbell says. "In Japan, FARs reach as high as 375 percent." A multi-story warehouse naturally requires different design solutions than a single-story facility. One approach for moving goods in and out of the higher floors is a pair of spiral truck ramps, one for upward-bound traffic and one for downward-bound. Another solution is to serve just one floor with a ramp, and the balance of the building with both pallet lifters and freight elevators to allow for storage of goods that don't move in and out as quickly. Because the upper levels of a multi-story warehouse must be engineered to bear heavy loads, a vertical warehouse can be more expensive to build than a one-story facility. If the cost of acquiring the land represents at least 50 percent of the total construction cost, going vertical is a good idea. "Many Asian markets, such as Tokyo and Osaka, Singapore, and certain Chinese markets, have reached that tipping point," Campbell says. American cities are nowhere near that tipping point, especially in the current economy with its depressed real estate prices. And certainly, Campbell concedes, recent trends in the United States have favored construction of mega-sized DCs on the outskirts of metropolitan areas. But that trend could reverse itself in favor of development closer to the urban core. A LIFT FOR LIFT TRUCKS Whether the warehouse occupies one story or more, you still need to move goods from one section of the building to another. Forklift trucks provide another focus for companies that want to make warehouse operations more efficient and economical. Some companies that operate large electric forklift fleets have been testing the use of hydrogen fuel cells to power them. Because they emit nothing but water vapor, these cells are environmentally friendly. And while it takes hours to recharge conventional batteries, refilling hydrogen cells takes just seconds. "Companies place a hydrogen tank outside the warehouse, and refuel the lift truck just as you would a car," Sisko says. Another plus is that a hydrogen fuel cell emits the same level of power all day. That's not true of a conventional battery. "As the battery begins to discharge, the power rating decreases. Less and less power is generated, and the lift truck slows down," Sisko explains. Whatever its power source, eventually a lift truck will need maintenance. A service to help lift truck fleet managers squeeze costs out of that area was launched last November by AmeriQuest Transportation, Coral Springs, Fla. Traditionally, AmeriQuest has focused its services outside the warehouse, providing fleet management and truck leasing to about 1,000 members, mainly commercial carriers and companies with private fleets. But when members repeatedly asked for help with their forklift fleets � particularly with buying parts, managing service, and buying whole units � AmeriQuest developed its new Materials Handling Services program, which includes lift truck parts procurement, lift truck fleet management, and lift truck remarketing. Companies that maintain their own lift trucks are candidates for the parts procurement service. Normally, these parts pass through three layers of suppliers -- parts manufacturers, lift truck manufacturers, and lift truck dealers -- before reaching the end user. "By the time an end user gets a part, it has been faced with three markups," says Scott Grushoff, vice president and general manager of AmeriQuest Materials Handling. To gain discounts for its members, AmeriQuest has negotiated agreements with parts manufacturers and large parts distributors. Members order the parts from AmeriQuest. "We cut lift truck dealers and Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) out of the equation," Grushoff says. "On average, members save more than 30 percent on the parts they buy." AmeriQuest's inventory includes replacement parts, batteries and chargers, tires and poly wheels, electric motors, and many electronic components. Warehouse operators who don't service their own lift trucks may sign up for AmeriQuest's fleet management service. When a member needs service, AmeriQuest dispatches a technician from an authorized provider, with which it has negotiated rates and established service standards. On site, the technician calls an AmeriQuest employee who is an expert on lift truck repair, and the two collaborate on the problem. "There's no open checkbook for the technician to do any repairs he deems necessary," Grushoff says. When the work is done, the repair service submits an invoice to AmeriQuest, which makes sure the vendor abides by the agreed rate and bills only for a reasonable amount of labor. Members also take advantage of AmeriQuest's rates for parts. At the end of the month, members receive a consolidated statement for all repairs performed. AmeriQuest monitors repair records to make sure service shops don't send inexperienced technicians who repeatedly misdiagnose problems. It ensures that equipment still under warranty is treated correctly. It also provides software that corporate managers can use to monitor lift truck usage and maintenance across all their locations. Under its third offering, AmeriQuest helps members find buyers for used forklift trucks. Although AmeriQuest charges a fee for some of its truck fleet management services, there is no fee for using any of the services in the Materials Handling program, Grushoff says. Building a Team No matter how green the building or efficient the processes, you can't run a warehouse without people. When employees on the floor pull together as a team, opportunities to improve the operation abound. One key to running a world-class warehouse is to develop a corporate culture in which management and employees share common values, says Ron Cain, president and CEO of third- party logistics provider (3PL) TMSi. A strong sense of community in the warehouse drives excellent performance because everyone's efforts are aligned. "There's a higher purpose than just showing up to work," Cain says. A non-asset-based 3PL based in Fernandina Beach, Fla., and Portsmouth, N.H., TMSi typically staffs and manages logistics inside its customers' facilities. For example, TMSi has been running parts warehouses in Jeffersonville, Ind., and Jacksonville, Fla., for General Electric since 2002 and one in Cranbury, N.J., since 2008. Distributors and technicians use these parts to service washers, dryers, refrigerators, and other major appliances. At each warehouse, GE provides the facility, the warehouse management system, and the customer orders, explains Edward Huttunen, parts distribution manager for GE in Louisville, Ky. TMSi, which staffs and manages the warehouse, is responsible for receiving, putaway, picking, shipping, arranging inbound and outbound transportation, and keeping inventory in good order and accurate. COMMUNITY SERVICE One strategy that TMSi's managers use to build team spirit on the warehouse floor is to encourage community service. In the GE facilities, the 3PL's employees have held food, clothing, and toy drives for charities that benefit children and have sometimes gone off site to volunteer for those organizations. "Collaborating for the sake of others encourages employees to feel like partners," Huttunen says. "It provides a different perspective of your fellow workers and generates camaraderie and strong bonds." Employees at other TMSi-run warehouses have participated in walk-a-thons, run after-school programs, and led students in renovating houses for the needy. "Those facilities always outperform the others," Cain says. Performance soars because public service projects get employees used to the idea of putting others first. "Once they do that, they become a true team built on trying to continue to improve," Cain says. That spirit spills over into the warehouse, where employees feel empowered to influence the culture and the processes. TMSi's efforts to strengthen corporate culture in the warehouse go beyond philanthropy. The 3PL treats employees like valuable team members, encouraging them to share ideas and information among themselves, with GE and with GE's customers. For example, when distributors and technicians visit a GE warehouse to learn about the operation, TMSi staff are on hand to explain how they fill orders. By the same token, TMSi includes floor staff in "action workouts" -- lean exercises in which GE's employees, customers, and distribution team collaborate to improve specific warehouse processes. Associates who work on the front lines have valuable insights, and they're thrilled when managers take their suggestions for improvement. This kind of collaborative corporate culture gives employees a sense of ownership. "Employees are all over any kind of problem that touches their area," Huttunen says. "An employee with that attitude will seek out information and follow through without prodding from management." In the current economic slump, when it's more important than ever to control costs, TMSi's teams have stepped up to the task. "They've worked with their associates and have been able to improve productivity through increased flexibility," Huttunen says. "They have also maintained a high-value proposition for our customers." FULL SPEED AHEAD "We're going to find a way to do it" could also be the cry of all logistics leaders who devise creative solutions for their warehouse operations. A smarter, faster, greener, more efficient warehouse puts a company in position to ride out tough times and keep speeding ahead. |

Cross-docking

Cross-docking

Cross-docking is a practice in logistics of unloading materials from an incoming semi-trailer truck or rail car and loading these materials directly into outbound trucks, trailers, or rail cars, with little or no storage in between. This may be done to change type of conveyance, to sort material intended for different destinations, or to combine material from different origins into transport vehicles (or containers) with the same, or similar destination.

Cross-Dock operations were first pioneered in the US trucking industry in the 1930's, and have been in continuous use in LTL (less than truckload) operations ever since. The US Military began utilizing cross-dock operations in the 1950's. Wal-Mart discovered the benefits of cross-docking in the retail sector in the late 1980's.

In the LTL trucking industry, cross-docking is done by moving cargo from one transport vehicle directly into another, with minimal or no warehousing. In retail practice, cross-docking operations may utilize staging areas where inbound materials are sorted, consolidated, and stored until the outbound shipment is complete and ready to ship.

Advantages of Retail Cross-Docking

- Streamlines the supply chain from point of origin to point of sale

- Reduces handling costs, operating costs, and the storage of inventory

- Products get to the distributor and consequently to the customer faster

- Reduces, or eliminates warehousing costs

- May increase available retail sales space

Typical applications

- "Hub and spoke" arrangements, where materials are brought in to one central location and then sorted for delivery to a variety of destinations

- Consolidation arrangements, where a variety of smaller shipments are combined into one larger shipment for economy of transport

- Deconsolidation arrangements, where large shipments (e.g. railcar lots) are broken down into smaller lots for ease of delivery.

Retail cross-dock example: Using the cross-dock technique, Wal-Mart was able to effectively leverage their logistical volume into a core strategic competency.

- Wal Mart operates an extensive satellite network of distribution centers serviced by company owned trucks

- Wal Mart’s satellite network sends point of sale (POS) data directly to 4,000 vendors.

- Each register is directly connected to a satellite system sending sales information to Wal Mart’s headquarters and distribution centers.

Factors influencing the use of retail cross-docks

- cross-docking is dependent on continuous communication between suppliers, distribution centers, and all points of sale.

- Customer and supplier geography -- particularly when a single corporate customer has many multiple branches or using points

- Freight costs for the commodities being transported

- Cost of inventory in transit

- Complexity of loads

- Handling methods

- Logistics software integration between supplier(s), vendor, and shipper

- Tracking of inventory in transit

Cross docking

Cross docking

Cross docking means to take a finished good from the manufacturing plant and deliver it directly to the customer with little or no handling in between. Cross docking reduces handling and storage of inventory, the step of filling a warehouse with inventory before shipping it out is virtually eliminated [1].

Simply, stated cross-docking, means receiving goods at one door and shipping out through the other door almost immediately without putting them in storage [2].

Cross docking shift the focus from "supply chain" to "demand chain". For example stock coming into cross docking center has already been pre-allocated against a replenishment order generated by a retailer in the supply chain [2].

Cross docking helps retailers streamline the supply chain from point of origin to point of sale [3].

It serves number of objectives. It helps reduce operating costs, increase throughput, reduces inventory levels, and helps in increase of sales space [2].

Cross docking helps reduce direct cost associated with excess inventory by eliminating unnecessary handling and storage of product. Less inventory means less space and equipment required for handling and storing the products. This also means reduced product damages and product obsolescence [3].

Cross docking also encourages electronic communications between retailers and their suppliers thus creating further opportunities for gains in efficiency [3].

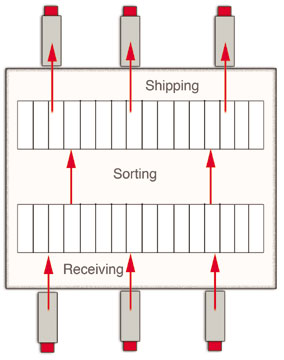

How cross-docking works?

On receiving goods workers put pallets in lanes corresponding to the receiving doors, a second team or workers sorts pallets into shipping lanes, from which a final team loads them into outbound trailers [4].

The following figure illustrates this:

Cross Docking at work

Source: http://web.nps.navy.mil/~krgue/Teaching/xdock-mba.pdf

Please note that this is a simplistic illustration of how cross docking works. Cross docking can take many forms like manufacturing cross docking, distributor cross docking, transportation cross docking, retail cross docking ( Wal-Mart uses this type) and opportunistic cross docking. Based on different classification exact execution of cross docking may vary. This discussion is beyond the scope of this text [4]. Please refer to http://web.nps.navy.mil/~krgue/Teaching/xdock-mba.pdf http://web.nps.navy.mil/~krgue/shape-submitted.pdf for more details.

Another interesting article is: Supply Chain Management the Wal-Mart Way

To read more about cross docking please go to Cross-docking: A common practice today, sure to grow tomorrow Modern Materials Handling; Boston; Mid-May 1998; Anonymous9

1. Cross docking: A common practice today, sure to grow tomorrow -- Modern Materials Handling; Boston;

2. http://www.dmg.co.uk/distribution/library/9804i.htm

3. http://www.colby.com.au/division/is/cs02.htm

4. CrossdockingL Just-In-Time for Distribution Kevin R. Gue Graduate School of Business & Public Policy Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA 93943 May 8, 2001 http://web.nps.navy.mil/~krgue/Teaching/xdock-mba.pdf

原文:http://projects.bus.lsu.edu/independent_study/vdhing1/othertopics/crossdocking.htm

Cross docking

Cross docking

Der Begriff Cross Docking bzw. Kreuzverkupplung bezeichnet eine Warenumschlagsart, bei der Waren vom Lieferanten (Absender) vorkommissioniert geliefert werden. Das bedeutet, dass der Einlagerungsprozess und die dazugehörige Aktivität des Bestandslagers entfallen.

Das konzeptionelle Gegenteil des Cross Dockings ist die sortenreine Anlieferung, Einlagerung und anschließende Kommissionierung von Waren in einem Warenlager.

Ziele [Bearbeiten]

Ziele des Cross-Dockings:

- Reduzierung der Lagerhaltungskosten

- Reduzierung der Anzahl der Prozessschritte

Cross-Docking-Varianten [Bearbeiten]

- Einstufiges System : Die Lieferanten kommissionieren die Waren (oder auch 'logistische Einheiten' genannt) bezogen auf den Endempfänger (Filialen oder Endkunden). Im einstufigen System werden die Waren 'wie vom Absender verpackt' über einen oder mehrere Umschlagpunkte an den Endempfänger weitergeleitet. Voraussetzung hierfür ist, dass der Absender die Waren (meist Paletten-weise) kennzeichnet - also die entsprechenden Endempfänger direkt auf/an der Ware angibt. Dieses Verfahren wird auch als Pre-Allocated Cross-Docking (PAXD) bezeichnet.

- Zweistufiges System (auch Transshipment genannt): Die Lieferanten kommissionieren bezogen auf den Umschlagpunkt oder Cross-Docking-Punkt. Im zweistufigen System werden die logistischen Einheiten unverändert nur bis zum Umschlagpunkt geleitet. Am Umschlagpunkt erfolgt dann der eigentliche Umschlag in neue logistische Einheiten, welche von diesem Zeitpunkt an an den Endkunden adressiert sind. Dieses Verfahren wird auch als Break-Bulk Cross-Docking (BBXD) bezeichnet.

- Mehrstufiges System: Ein mehrstufiges System beinhalten noch weitere Prozessschritte neben der eigentlichen Umkommissionierung. Diese können bspw. die Konfektionierung von Artikeln oder sog. Value Added Services sein. Das Zweistufige System ist somit nur als Spezialfall des mehrstufigen Systems zu sehen.

Cross Docking

Cross Docking: Is it right for me?

This article is the first in a series of articles on the subject of cross docking.

Judging by the number of inquiries we receive relative to inventory management in distribution, a look at cross docking practices seems to make sense. This will be the first of a series of briefs on cross docking, how and where it works, and a look at some best practice ideas that might be useful to those of you in the distribution business (of all sizes). I’ll also be providing you links to some excellent online references for more information.

Judging by the number of inquiries we receive relative to inventory management in distribution, a look at cross docking practices seems to make sense. This will be the first of a series of briefs on cross docking, how and where it works, and a look at some best practice ideas that might be useful to those of you in the distribution business (of all sizes). I’ll also be providing you links to some excellent online references for more information.

Most everyone is familiar with how those like Wal-Mart took the cross docking model, and essentially redefined supply chain efficiency. The results achieved are well-documented. For those of us involved with mid-size organizations, a compelling case can be made for considering cross dock principles in our distribution centers. If you are able to move material from receiving dock to shipping dock, and bypass storage, consider what you gain. Costs associated with holding inventory, protecting it, insuring it, picking it, counting it, and so forth.

Although the “cross docking” term is well ingrained in our supply chain lingo, it is important to understand the concept also applies elsewhere in our distribution centers (more on that later), notwithstanding what you call it. Let’s begin.

Inventory is the Real Issue

We all deal with a variety of costs in our supply chains. At the top of your list and my list are order-picking costs and inventory holding costs. Your goal is to minimize or eliminate both. In addition, freight cost reductions can also represent significant potential, particularly for those dealing with LTL’s and small package carriers. Most of you, who get this right, are using tools to better manage information, and to better manage or coordinate with your supplier chain partners. It is not necessary to be large in size to take advantage of a cross dock model. Many of today’s solutions are both modular and scalable. These tools allow you, the distributor, to better consolidate your shipments and shorten your cycle time.

Most of you deal with products from multiple vendors which enter your distribution centers. These products are typically not ready for direct transfer to your shipping docks. As a result, you must create a label for the product upon receipt, and then move the product to the correct shipping area. This increases costs because a non-value add touch point(s) is required. Essentially, the question is who does the work to prepare the product for shipment. We both would rather the vendor handle it, but that is not always reality. In our case, we scan the incoming shipment, a lookup is performed, and a new label is created and applied to the product, readying it for shipment. This approach is known by various names, one of which is “post-distribution”. If you negotiate with your vendors to label products that can be cross-docked directly to your shipping area, then you will see terms like, “transshipment ready”, “transload ready”(an incorrect usage), or “pre-distribution”.

When does cross docking begin to make sense? Begin with considering the order profiles of your key customers. Like us, you may have many customers who tend to order the same products in significant volumes throughout the year, or at least seasonally. In effect, supply and demand are pretty much predictable, allowing you to match each with the other. Begin with these products as candidates. Some products will be filtered out of this mix. For instance, those that require excessive handling in order to move, or products of an unusual shape, size, or excessive weight would be examples. Also, products that are FIFO, or date-sensitive make poor candidates.

When you engage in a supply chain enhancement such as cross docking, the players both upstream and downstream of you play key roles. In fact, they will define your success or failure. Our experience is that all can benefit when all are involved. Otherwise, you may simply be going through an exercise in which some costs are passed off to another link in the supply chain.

In upcoming briefs, we will look at the following areas. You are welcome to comment below with any questions or comments.

- Am I wasting my time……is this a viable consideration for my company?

- Cross dock layout alternatives that work

- Getting started……understanding a simple system (and costs)

Am I wasting time: is cross-docking a viable consideration for my company?

This article is the second in a series of articles on cross docking

In concept and on paper cross docking looks great, but, what about actual implementation? What kind of return do we get on this investment? The short answer is the implementation can be challenging. However, with planning, a committed team of upstream and downstream participants, and possibly even a pilot program, it can pay significant benefits.

Cross docking does not have to be complicated. Some, even today, execute cross-docking using human-readable paper documentation as the driver. As mentioned in the original brief, cross docking can cover a wide range of distribution activities. In one door and directly out the other is one approach. Many cross dockers also add value in the brief (hopefully) interval between receiving and shipping. Others send product to a temporary buffer in the interval, in many of these cases an automated system (mini-load, AS/RS, etc.) serves as the buffer.

What might we potentially expect from a successful implementation?

- Reduction in capital investment in facilities and equipment (less space required)

- Reduction in inventory

- Reduction in personnel requirements

- Reduction in order cycle time

- Reduction in product damage (reduced touches)

- Reduction in freight costs

What are the gotchas, why we might fail?

- Facility layout is poor

- Internal information systems are not integrated

- Little or no integration and collaboration within your supply chain

- Compliance by all supply chain partners

- Selected the wrong products

- Reliable suppliers (accurate, on time deliveries)

- Sufficient volume of activity

- Understanding peak workload variations

Information will make you or break you

To best manage your inventory, you really need visibility into what you will be receiving, before receiving it. Advance Shipping Notices (ASN) are what provide this visibility.

Most of you are familiar with these, and probably already use them in some form. With ASN’s, you know what is arriving and when. With your Warehouse Management System (WMS) you know what is in your warehouse. Marry these with your order management system and you have the information necessary to match current inventory with order requirements, and get orders out the door efficiently (transportation covered shortly) You begin to see the need for cooperation and communication across the supply chain. The value (necessity) of EDI or internet connectivity becomes apparent. A level of information infrastructure is a must.

Supply chain partners are just that, partners in an integrated cross dock process. Select those that deliver products frequently, and deliver them on time. Most of you already have a solid handle on who are possible vendor partners, those with whom you are currently highly collaborative. Those whose products require a very limited number of touch points in the cross dock, if any touch points at all.

Touch points are work. Who does the work?

As a distributor or cross docker, identifying who “preps the products” for shipment is a fundamental consideration. For instance, incoming products were pre-labeled by the vendor for outgoing shipment (they did the work). Alternatively, the incoming products require labeling on your dock prior to outgoing shipment (you do the work). A third case might be the incoming products have been pre-labeled, but might need something additional, such as de-palletizing before outgoing shipment (we both do some work). A good answer to, “Who does what?” is “Who can do it most efficiently in the supply chain?”

Organizations that are process-driven, with a continuous process improvement mentality fit well in a cross dock environment. They tend to establish metrics, measure, and effectively use feedback for improvement. Those achieving high levels of efficiency will track and trace products throughout the entire supply chain to capture data which drives these improvements. Ongoing emphasis on training and education plays a key role.

In our next brief, we will touch on transportation, and then move into facility layout alternatives, what works, what does not, and links to a couple of good case studies and online tools. You are welcome to e-mail me with any questions or comments.

Upcoming briefs:

- Cross dock layout alternatives that work

- Getting started understanding a simple system (and costs)

Resources for additional information on cross docking. Both are worth a look.

- Warehousing and Education Research Council’s (www.werc.org) guide to cross docking: Making the Move to Cross Docking

- Kevin Gue, Professor, Graduate School of Business and Public Policy, Naval Postgraduate School, numerous articles, research, and tools with a focus on cross docking (http://www.scivis.nps.navy.mil/~krgue/index.html)

Cross Docking: What are the facility layout considerations?

This is the third in a series of articles on cross docking

If you started from scratch, many might simply build a cross dock facility with a much shallower depth than most warehouses. A depth of a hundred feet or so, with incoming product on one side that can be easily moved a short distance and loaded on the other side to an outbound truck. Most of us however, must deal with an existing facility, many times a large square box which is not generally the preferred layout. However, as long as the existing facility has a sufficient quantity of dock doors, yard space, and an adequate footprint, you may be fine…

Simply having a lot of dock doors does little for efficiency if the doors are located on opposite walls at a great distance from one another. Conveyor companies might love this, but there are better alternatives. Some recommend all the doors on one wall, or even at 90 degrees to one another. High speed movers would then travel between incoming and outgoing doors in closest proximity to one another. Proximity of high traffic incoming and outgoing doors is key. Distance equals costs. Many consider dedicating only a portion of their facility for cross dock duties as an acceptable workaround.

Pallet handling versus case handling create separate requirements. Congestion in dock areas will be a killer. Sufficient dock space is key to moving products quickly and safely. This is particularly true if the company is growing or deals with seasonal products. Ample space must be available for any pallet staging activities near shipping doors. If aisles are part of your logical pathways, then oversize them in high traffic areas.

One of the more complete reviews of cross dock design is by John Bartholdi and Kevin Gue in Transportation Science. They provide an analysis of the impact of “shape” on the performance of a cross dock operation. They considered a wide variety of designs and freight flow patterns, and offered the following summary:

“Shape matters. Freight must be moved across the dock and total distance traveled is a good estimate of labor costs. The best shape for small to mid-sized cross docks is a narrow rectangle or I-shape, which gets maximum use of its most central doors. For larger docks, alternative shapes are more attractive. The best shapes for larger docks will have piers branching out from a central area. These designs have more corners, for which they pay a cost. However, they achieve greater centrality, and so more distant doors are closer to other doors. For example, the T-shape is best for dock sizes between about 150 to 200 doors. For larger than 200 doors, the X-shape is best. Despite having four inside corners near the center of the dock, the worst doors are not far from the center. When freight flows are concentrated among few destinations, the point will be deferred at which a more complicated design becomes attractive. This is because the labor will be concentrated on a subset of the dock, and so the dock is, in effect, a smaller dock.”

Layouts designed on solid principles will address the “layout issue”. Although we have been focusing on the internal logistics of cross docking, we do need to make note of another obvious area of interest…. the “trailer spotting” issue. A poor spotting process defeats a quality layout. They work in concert. There are many issues you deal with in creating an optimum design for cross docking. In the next brief, we will take a look at cross docking in actual practice. This will include a couple of applications that deal with the issues we have discussed, and others. One application is complex, the other is a simple scalable system (actually including system costs).

Cross Docking: A retailer improves supply chain

This is the fourth in a series of briefs on cross docking

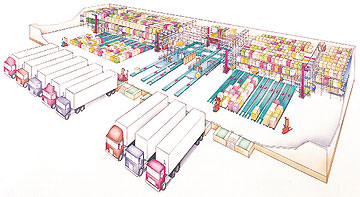

A recent project for a large retailer in the Southwest provided a good example of how an element of cross-docking might be deployed to reduce the footprint of distribution space required, reduce order fulfillment touchpoints, and shorten the logical pathway for fulfilling orders.

Incoming shipments are anticipated through the use of advanced shipping notices (ASN’s). Stretch-wrapped pallet loads arrive via truck throughout the day. They arrive at doors designated for cross-docking. These doors were selected based upon proximity to the material handling system which takes advantage of the facility layout. Pallets are unloaded by fork truck, the stretch wrap removed, and cases manually inducted into one of several conveyor staging lanes. Each lane represents a “wave” of orders which will be processed either that day, or a specific day later in the week. When a wave is released, it moves downstream, and the individual cases are sorted to a specific shipping lane whose products are destined for a particular store. Other products from static storage positions and non-conveyables destined for the same store are consolidated at this point.

As waves are released, the staging lane becomes immediately available for a subsequent wave. Multiple waves are processed daily. Pallets arrive at the receiving docks with man-readable labels indicating the destination store and day to ship. The individual cases on each pallet are pre-labeled (pre-distribution) with a unique identifier that corresponds to the ultimate destination retail store, the SKU number, and the quantity. When the case label is scanned for the identifier, a lookup into a warehouse control system database occurs, which provides the routing instructions, ie, the correct shipping door. Again, orders can be comprised of cases that are cross-docked from the staging lanes, product stored in static storage positions, and/or non-conveyables. The sortation management system routes all conveyables in the current wave directly to the correct shipping lane.

Order fulfillment occurs in waves, due to a limited number of shipping doors. Most shipping doors are dedicated to a specific destination store, while a handful of other doors will each serve a number of smaller retail stores. This distribution center demonstrates how cross-docking products that are good candidates, can be integrated with order fulfillment of inventoried products to enhance overall distribution performance.

Next month we will look at a scalable, “out-of-the-box” cross docking system, its layout, and cost to purchase and implement. It will include conveyors, controls, and software to support a basic cross docking system. We have taken a modular approach to a systems solution that can truly be modularized. Join us.