Case history

In search of the perfect battery

Mar 6th 2008

From The Economist print edition

Energy technology: Researchers are desperate to find a modern-day philosopher's stone: the battery technology that will make electric cars practical. Here is a brief history of their quest

Getty Images

WHEN General Motors (GM) launched the EV1, a sleek electric vehicle, with much fanfare in 1996, it was supposed to herald a revolution: the start of the modern mass-production of electric cars. At the heart of the two-seater sat a massive 533kg lead-acid battery, providing the EV1 with a range of about 110km (70 miles). Many people who leased the car were enthusiastic, but its limited range, and the fact that it took many hours to recharge, among other reasons, convinced GM and other carmakers that had launched all-electric models to abandon their efforts a few years later.

Yet today about a dozen firms are once again developing all-electric or plug-in hybrid vehicles capable of running on batteries for short trips (and, in the case of plug-in hybrids, firing up an internal-combustion engine for longer trips). Toyota's popular Prius hybrid, by contrast, can travel less than a mile on battery power alone. Tesla Motors of San Carlos, California, recently delivered its first Roadster, an all-electric two-seater with a 450kg battery pack and a range of 350km (220 miles) between charges. And both Toyota and GM hope to start selling plug-in hybrids as soon as 2010.

So what has changed? Aside from growing concern about climate change and a surge in the oil price, the big difference is that battery technology is getting a lot better. Rechargeable lithium-ion batteries, which helped to make the mobile-phone revolution possible in the past decade, are now expected to power the increasing electrification of the car. “They are clearly the next step,” says Mary Ann Wright, the boss of Johnson Controls-Saft Advanced Power Solutions, a joint venture that recently opened a factory in France to produce lithium-ion batteries for hybrid vehicles.

According to Menahem Anderman, a consultant based in California who specialises in the automotive-battery market, more money is being spent on research into lithium-ion batteries than all other battery chemistries combined. A big market awaits the firms that manage to adapt lithium-ion batteries for cars. Between now and 2015, Dr Anderman estimates, the worldwide market for hybrid-vehicle batteries will more than triple, to $2.3 billion. Lithium-ion batteries, the first of which should appear in hybrid cars in 2009, could make up as much as half of that, he predicts.

Compared with other types of rechargeable-battery chemistry, the lithium-ion approach has many advantages. Besides being light, it does not suffer from any memory effect, which is the loss in capacity when a battery is recharged without being fully depleted. Once in mass production, large-scale lithium-ion technology is expected to become cheaper than its closest rival, the nickel-metal-hydride battery, which is found in the Prius and most other hybrid cars.

Still, the success of the lithium-ion battery is not assured. Its biggest weakness is probably its tendency to become unstable if it is overheated, overcharged or punctured. In 2006 Sony, a Japanese electronics giant, had to recall several million laptop batteries because of a manufacturing defect that caused some batteries to burst into flames. A faulty car battery which contains many times more stored energy could trigger a huge explosion—something no car company could afford. Performance, durability and tight costs for cars are also much more stringent than for small electronic devices. So the quest is under way for the refinements and improvements that will bring lithium-ion batteries up to scratch—and lead to their presence in millions of cars.

Alessandro Volta, an Italian physicist, invented the first battery in 1800. Since then a lot of new types have been developed, though all are based on the same principle: they exploit chemical reactions between different materials to store and deliver electrical energy.

Back to battery basics

A battery is made up of one or more cells. Each cell consists of a negative electrode and a positive electrode kept apart by a separator soaked in a conductive electrolyte that allows ions, but not electrons, to travel between them. When a battery is connected to a load, a chemical reaction begins. As positively charged ions travel from the negative to the positive electrode through the electrolyte, a proportional number of negatively charged electrons must make the same journey through an external circuit, resulting in an electric current that does useful work.

“Compared with computer chips, battery technology has improved very slowly over the years.”

Some batteries are based on an underlying chemical reaction that can be reversed. Such rechargeable batteries have an advantage, because they can be restored to their charged state by reversing the direction of the current flow that occurred during discharging. They can thus be reused hundreds or thousands of times. According to Joe Iorillo, an analyst at the Freedonia Group, rechargeable batteries make up almost two-thirds of the world's $56 billion battery market. Four different chemical reactions dominate the industry—each of which has pros and cons when it comes to utility, durability, cost, safety and performance.

The first rechargeable battery, the lead-acid battery, was invented in 1859 by Gaston Planté, a French physicist. The electrification of Europe and America in the late 19th century sparked the use of storage batteries for telegraphy, portable electric-lighting systems and back-up power. But the biggest market was probably electric cars. At the turn of the century battery-powered vehicles were a common sight on city streets, because they were quiet and did not emit any noxious fumes. But electric cars could not compete on range. In 1912 the electric self-starter, which replaced cranking by hand, meant that cars with internal-combustion engines left electric cars in the dust.

Nickel-cadmium cells came along around 1900 and were used in situations where more power was needed. As with lead-acid batteries, nickel-cadmium cells had a tendency to produce gases while in use, especially when being overcharged. In the late 1940s Georg Neumann, a German engineer, succeeded in fine-tuning the battery's chemistry to avoid this problem, making a sealed version possible. It started to become more widely available in the 1960s, powering devices such as electric razors and toothbrushes.

For most of the 20th century lead-acid and nickel-cadmium cells dominated the rechargeable-battery market, and both are still in use today. Although they cannot store as much energy for a given weight or volume as newer technologies, they can be extremely cost-effective. Small lead-acid battery packs provide short bursts of power to starter motors in virtually all cars; they are also used in large back-up power systems, and make up about half of the worldwide rechargeable-battery market. Nickel-cadmium batteries are used to provide emergency back-up power on planes and trains.

Time to change the batteries

In the past two decades two new rechargeable-battery types made their commercial debuts. Storing about twice as much energy as a lead-acid battery for a given weight, the nickel-metal-hydride battery appeared on the market in 1989. For much of the 1990s it was the battery of choice for powering portable electronic devices, displacing nickel-cadmium batteries in many applications. Toyota picked nickel-metal-hydride batteries for the new hybrid petrol-electric car it launched in 1997, the Prius.

Nickel-metal-hydride batteries evolved from the nickel-hydrogen batteries used to power satellites. Such batteries are expensive and bulky, since they require high-pressure hydrogen-storage tanks, but they offer high energy-density and last a long time, which makes them well suited for use in space. Nickel-metal-hydride batteries emerged as researchers looked for ways to store hydrogen in a more convenient form: within a hydrogen-absorbing metal alloy. Eventually Stanford Ovshinsky, an American inventor, and his company, now known as ECD Ovonics, succeeded in creating metal-hydride alloys with a disordered structure that improved performance.

Adapting the nickel-metal-hydride battery to the automotive environment was no small feat, since the way batteries have to work in hybrid cars is very different from the way they work in portable devices. Batteries in laptops and mobile phones are engineered to be discharged over the course of several hours or days, and they only need to last a couple of years. Hybrid-car batteries, on the other hand, are expected to work for eight to ten years and must endure hundreds of thousands of partial charge and discharge cycles as they absorb energy from regenerative braking or supply short bursts of power to aid in acceleration.

Lithium-ion batteries evolved from non-rechargeable lithium batteries, such as those used in watches and hearing aids. One reason lithium is particularly suitable for batteries is that it is the lightest metal, which means a lithium battery of a given weight can store more energy than one based on another metal (such as lead or nickel). Early rechargeable lithium batteries used pure lithium metal as the negative-electrode material, and an “intercalation” compound—a material with a lattice structure that could absorb lithium ions—as the positive electrode.

The problem with this design was that during recharging, the metallic lithium reformed unevenly at the negative electrode, creating spiky structures called “dendrites” that are unstable and reactive, and can pierce the separator and cause an explosion. So today's rechargeable lithium-ion batteries do not contain lithium in metallic form. Instead they use materials with lattice structures for both positive and negative electrodes. As the battery discharges, the lithium ions swim from the negative-electrode lattice to the positive one; during recharging, they swim back again. This to-and-fro approach is called a “rocking chair” design.

The first commercial lithium-ion battery, launched by Sony in 1991, was a rocking-chair design that used cobalt oxide for the positive electrode, and graphite (carbon) for the negative one. In the early 1990s, such batteries had an energy density of about 100 watt-hours per litre. Since then engineers have worked out ways to squeeze more than twice as much energy into a battery of the same size, in particular by reducing the width of the separator and increasing the amount of active electrode materials.

The high energy-density of lithium-ion batteries makes them the best technology for portable devices. According to Christophe Pillot of Avicenne Développement, a market-research firm based in Paris, they account for 70% of the $7 billion market for portable, rechargeable batteries. But not all lithium-ion batteries are alike. The host structures that accept lithium ions can be made using a variety of materials, explains Venkat Srinivasan, a scientist at America's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. The combination of materials determines the characteristics of the battery, including its energy and power density, safety, longevity and cost. Because of this flexibility, researchers hope to develop new electrode materials that can increase the energy density of lithium-ion batteries by a factor of two or more in the future.

Hooked on lithium

The batteries commonly used in today's mobile phones and laptops still use cobalt oxide as the positive electrode. Such batteries are also starting to appear in cars, such as Tesla's Roadster. But since cobalt oxide is so reactive and costly, most experts deem it unsuitable for widespread use in hybrid or electric vehicles.

So researchers are trying other approaches. Some firms, such as Compact Power, based in Troy, Michigan, are developing batteries in which the cobalt is replaced by manganese, a material that is less expensive and more stable at high temperatures. Unfortunately, batteries with manganese-based electrodes store slightly less energy than cobalt-based ones, and also tend to have a shorter life, as manganese starts to dissolve into the electrolyte. But blending manganese with other elements, such as nickel and cobalt, can reduce these problems, says Michael Thackeray, a senior scientist at America's Argonne National Laboratory who holds several patents in this area.

In 1997 John Goodenough and his colleagues at the University of Texas published a paper in which they suggested using a new material for the positive electrode: iron phosphate. It promised to be cheaper, safer and more environmentally friendly than cobalt oxide. There were just two problems: it had a lower energy-density than cobalt oxide and suffered from low conductivity, limiting the rate at which energy could be delivered and stored by the battery. So when Yet-Ming Chiang of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and his colleagues published a paper in 2002 in which they claimed to have dramatically boosted the material's conductivity by doping it with aluminium, niobium and zirconium, other researchers were impressed—though the exact mechanism that causes the increase in performance has since become the subject of a heated debate.

Dr Chiang's team published another paper in 2004 in which they described a way to increase performance further. Using iron-phosphate particles less than 100 nanometres across—about 100 times smaller than usual—increases the surface area of the electrode and improves the battery's ability to store and deliver energy. But again, the exact mechanism involved is somewhat controversial.

The iron-phosphate technology is being commercialised by several companies, including A123 Systems, co-founded by Dr Chiang, and Phostech Lithium, a Canadian firm that has been granted exclusive rights to manufacture and sell the material based on Dr Goodenough's patents. At the moment the two rivals are competing in the market, but their fate may be decided in court, since they are fighting a patent-infringement battle.

The quest for the perfect battery

Johnson Controls and Saft, which launched a joint venture in 2006, are taking a different approach, in which the positive electrode is made using a nickel-cobalt-aluminium-oxide. John Searle, the company's boss, says batteries made using its approach can last about 15 years. In 2007 Saft announced that Daimler had selected its batteries for use in a hybrid Mercedes saloon, due to go on sale in 2009. Other materials being investigated for use in future lithium-ion batteries include tin alloys and silicon.

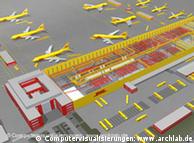

Corbis Look, no exhaust pipe

Look, no exhaust pipe At this point, it is hard to say which lithium-ion variation will prevail. Toyota, which is pursuing its own battery development with Matsushita, will not say which chemistry it favours. GM is also hedging its bets. The company is testing battery packs from both A123 Systems and Compact Power for the Chevy Volt (pictured), a forthcoming plug-in hybrid that will have an all-electric range of 40 miles and a small internal-combustion engine to recharge its battery when necessary. To ensure that the Volt's battery can always supply enough power and meet its targeted 10-year life-span, it will be kept between 30% and 80% charged at all times, says Roland Matthe of GM's energy-storage systems group.

GM hopes to start mass-production of the Volt in late 2010. That is ambitious, since the Volt's viability is dependent on the availability of a suitable battery technology. “It's either going to be a tremendous victory, or a terrible defeat,” says James George, a battery expert based in New Hampshire who has followed the industry for 45 years.

“We've still got a long way to go in terms of getting the ultimate battery,” says Dr Thackeray. Compared with computer chips, which have doubled in performance roughly every two years for decades, batteries have improved very slowly over their 200-year history. But high oil prices and concern over climate change mean there is now more of an incentive than ever for researchers to join the quest for better battery technologies. “It's going to be a journey”, says Ms Wright, “where we're going to be using the gas engine less and less.”

Monitoring the conditions: This sensor, a prototype developed by the Networked Embedded Computing group at Microsoft Research, is sensitive to heat and humidity. The group envisions using sensors like these to monitor servers in data centers, enabling significant energy savings. The sensors could also be used in homes to manage the energy use of appliances.

Monitoring the conditions: This sensor, a prototype developed by the Networked Embedded Computing group at Microsoft Research, is sensitive to heat and humidity. The group envisions using sensors like these to monitor servers in data centers, enabling significant energy savings. The sensors could also be used in homes to manage the energy use of appliances.